Southeast Asia should be well-positioned to thrive in a more geopolitically complex world. The region is rich in natural resources, has a young and increasingly wealthy population, and maintains economic and trade links with major economic powers like the U.S., China, India, and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

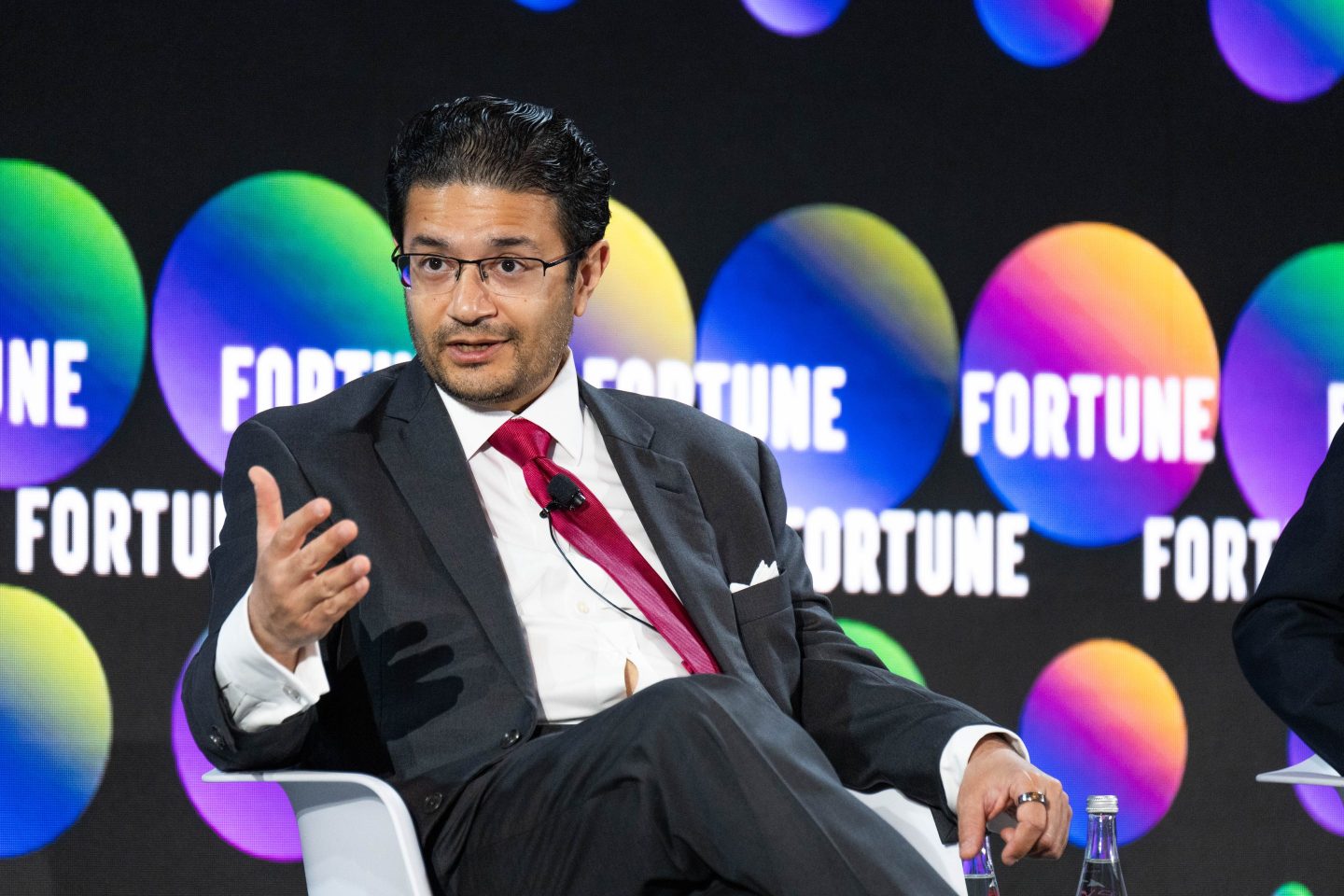

Yet during the Fortune Innovation Forum in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on Tuesday, Asia Partners cofounder Nicholas Nash challenged Southeast Asian entrepreneurs to be much more ambitious in their aims.

“We’re not thinking big enough,” he said, in response to a question about how talent is moving around the region. “If Southeast Asian talent can be attached to companies that can scale beyond 40, 50 or 100 billion [dollars’ worth] of market cap, they will stay.”

The only way to get to that level, Nash argued, is consolidation. “Not one of our countries in ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] is big enough to produce a multibillion-dollar company,” he said, noting that fewer than 10 companies in Southeast Asia had a market value worth just 1% of Nvidia’s $4.6 trillion.

Southeast Asia’s most valuable company is the Singaporean bank DBS, which has a market value of $116 billion. That’s merely a fraction of the total worth of Asia’s most valuable company, Taiwanese chipmaker TSMC. Just seven Southeast Asia–based companies are on this year’s Global 500, Fortune’s annual ranking of the world’s largest companies by revenue; China, by comparison, has 124 firms on the list.

“Considering the short lifespans we have, would you rather attach yourself to a company that could become a three or four trillion dollar company, or a company that could become a two or three billion dollar company?” Nash asked.

Nash’s concerns about talent were matched by Dato’ Seri Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association. The Southeast Asian country has been part of semiconductor supply chains for decades, ever since Intel opened its first non-U.S. plant in Penang in 1972. (Some of the world’s largest chip companies, like Broadcom and Intel, are now led by CEOs with roots in Malaysia.)

“Singapore gives out ASEAN scholarships, and our people just go there. Even when we don’t take the scholarships, they still hire our Malaysian talent,” Wong said. “Today, we don’t just have Singapore, we have China, Taiwan, and the rest of the world trying to take our talent.”

Wong put a positive spin on this competition: “This tells me that we have the talent,” he said. “How do we create ‘the Malaysian Dream’ like ‘the American Dream,’ where you can get all these opportunities in Malaysia?”