If Mauro Porcini’s mother had had her way, Samsung Electronics’ head designer wouldn’t have gone into design at all. “She wanted me to be a priest,” the Italian-born Porcini says, as he sits in his new office at Samsung’s R&D center, just outside Seoul’s buzzy Gangnam district, on a frigid December morning.

Porcini did not take his mother’s advice and join the priesthood. But he does see his current job in corporate design as something like a higher calling.

“It felt like faith, God, or whatever you believe in was looking down and saying, ‘Wait a second—before going after your dream, you need to prepare yourself. You need to be ready,’” Porcini says.

Porcini is more than ready for his new job as Samsung Electronics’ chief design officer, which he started last year. The 50-year-old has corporate design credentials few can match. He’s served as design chief at 3M and PepsiCo and started his career as a product designer at Philips. Now, at Samsung, he has what he considers a “dream job” in tech, right as “tech is about to completely change the way we live,” he says.

Samsung has long relied on a vast internal design workforce to become a brand whose smartphones rival Apple’s in capability and prestige. But lately, fresh competition from established players and new Chinese entrants is encroaching on Samsung’s former strength. AI, too, is forcing the company to rethink what today’s devices can do.

And so Samsung has turned to an outsider—Porcini—as its first-ever chief design officer to conceive of AI-powered products that resonate with consumers of all stripes and to give the Korean giant a more consistent, global voice.

Samsung and Porcini have been cagey about what exactly Porcini will do as chief design officer. The press release announcing his hiring said he will bolster the company’s “user-centered approach to design innovation,” and the company has stated the designer will work on its phones and home appliances.

Porcini, for his part, framed his mission as addressing a key set of questions:

“How can we evolve our portfolio to be as meaningful as possible to people and to the business? How can we create the best possible products? What is their identity? How do people interact with them?”

Turning to Porcini for those answers is a continued bet on human design by Samsung, even as cost pressures and new technologies could limit the appetite for designers elsewhere.

In 2011, Porcini became the first-ever chief design officer for 3M, home of goods like Post-its and Scotch tape. He had climbed the ranks of the American company for nearly a decade, starting as a Europe-based designer in 2002 and rising to head of global design, based in Milan. From there, he helped 3M win many of its first design awards, for products like a video projector with an innovative method of showing images and a welding helmet that was 35% lighter. In 2011, Porcini made the move to 3M’s headquarters in St. Paul to serve as the company’s first C-suite designer.

Porcini recalls telling executives at 3M that aesthetics needed to be incorporated into all its processes. “If I was making beautiful and functional products in ugly packaging, or if the experience in retail or digital was wrong, we were going to go nowhere,” he says. Porcini talked with retailers to make sure products were showcased “in the proper way.”

“It wasn’t easy, because it wasn’t in my job description,” he says. “I pissed off so many people.”

Then PepsiCo poached Porcini to be its first chief design officer in 2012. Porcini’s first job there—which he described in 2023 as a “baptism of fire”—was fixing the company’s new soda dispenser. Archrival Coca-Cola had launched its popular Freestyle dispenser, which allowed users to choose among a hundred different fountain drinks. Yet Pepsi’s attempt at a follow-up was more expensive and clunky. Porcini and his team responded with the Spire: a smaller soda dispenser that achieved the same results as Coke’s Freestyle with cheaper technology and a large screen, perfect for attracting customers.

Porcini’s other claim to fame at PepsiCo? Trashing a widely panned logo—a much-mocked memo explaining the design cited the “gravitational pull of Pepsi”—in favor of a more retro look.

Porcini says he got “a full immersion in branding and how to build iconic brands” during his decade at PepsiCo. “Industrial designers in tech, historically, focus on the product. What I learned in consumer packaged goods was the importance of the overall experience with the brand.”

Both 3M and PepsiCo gave Porcini an appreciation for what non-designers bring to the conversation. “The ideal configuration is one where you have designers coming in with a human-centric approach; you have marketing coming in with a business perspective; and R&D coming in with a technology perspective,” he says.

Porcini seems slightly out of place in the Korean chaebol’s offices. Hailing from Gallarate, a small town outside Milan, Porcini wears plaid trousers with white stripes down the side, platform boots, and a beige jacket with red lapels—a contrast to the more plainly dressed Korean designers and office workers who sit at Samsung desks. (He dressed slightly differently, but just as sharply, for our photo shoot.) Porcini says his clothes are a way to express his individuality in the boardroom: “This is what designers do…They look at reality, they look at their world, and have a unique and original point of view on what they need to do,” he told Fast Company last year, after the publication dubbed him one of its “Best Dressed in Business.”

Porcini’s original point of view is what Samsung wants—and arguably what it needs.

Samsung Electronics, founded in 1968, is the flagship company of the massive Samsung chaebol, one of the mega-conglomerates that dominate South Korea’s economy. At No. 27, Samsung Electronics is the highest-ranked Korean company on the Global 500, Fortune’s ranking of global companies by revenue. While Samsung’s smartphones are perhaps its most prominent product, the company makes televisions, computer monitors, refrigerators, washing machines, and other consumer electronic products. It also regularly appears on the annual Fortune World’s Most Admired Companies list, which is based on surveys of executives at leading U.S. and global companies.

Samsung Electronics is also a major supplier to other technology companies, including Apple, its archrival in the smartphone business, making batteries, camera modules, and memory chips. (Samsung’s chip business is historically its most profitable division.)

Samsung has reinvented itself several times over. In 1993, thenchairman Lee Kun-hee, during a business trip in Europe, summoned hundreds of executives to Frankfurt and pushed them to reinvigorate the company. “If you are to change, change completely…Change everything except your wife and children,” he told the crowd in what became known as the “Frankfurt Declaration.” Two years later, in 1995, Lee ordered his employees to destroy 150,000 Samsung mobile phones as a statement against their poor quality.

Lee made design a key part of Samsung’s ethos going forward, resulting in products like its 2002 T100 phone, the first to feature a color LCD display. Koreans dubbed it the “Lee Kun-hee” phone; the model sold 10 million units in its first year.

“Chairman Lee was one of a few business leaders who really understood the power of design and its potential value for the digital technologies he was pursuing,” says Youngjin Yoo, a professor of digital innovation at the London School of Economics and a former advisor to Samsung in the mid-2010s.

In fact, when Porcini brought PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi on a global tour to meet leaders in design, he made a stop at Samsung.

“We came all the way to Seoul in 2013 to meet the top management of Samsung and really understand how it was investing in design,” he recalls. Porcini highlights two dynamics at Samsung: a constant push to reinvent and revitalize its products, and “uniting the entire organization around one design mission.”

“Designers are the ambassadors for human beings. And creating value for humans is one of the most powerful competitive advantages you can build.”

Mauro Porcini, Chief Design Officer, Samsung Electronics

Samsung designers study how consumers use products. Take televisions: Samsung executives assumed customers cared only about video and audio quality, and not how the TV looked. Samsung’s designers argued otherwise: A TV spends more time off than on—making the TV more like a piece of furniture than a source of entertainment. Enter the 2006 Bordeaux LCD TV, with its wineglass-inspired design. During the interview, Porcini points to what looks like a reproduction of Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory behind him; in reality it’s Samsung’s Frame TV, which is meant to look like a painting. “Did you know that’s a TV?” he asks.

The Korean company now looks like an exception to “the innovator’s dilemma,” as coined by business theorist Clayton Christensen in 1997, which posits that incumbents often struggle with disruptive technologies, focusing instead on making their existing products better. Startups, on the other hand, have more space to refine and iterate their ideas until, eventually, they outcompete their larger brethren.

“The innovator’s dilemma, or creative destruction, is understood to be the normal way of doing business,” says Mehran Gul, author of The New Geography of Innovation. “One wave of companies gets replaced by the next, and then the next, and that’s why we barely talk about companies like IBM anymore.”

That has not been the case in South Korea, where the existing chaebols have managed to keep up with the times. “Companies like Samsung are as old as the IBMs, but they’ve managed to adapt to one technological wave after the other,” Gul says.

Still, Samsung has long had to battle accusations of being a fast follower or, worse, a copycat. Apple in 2011 sued Samsung for violating four of its iPhone design patents. Samsung countersued, and the legal battles escalated to dozens of lawsuits involving several companies, with one case even reaching the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016. Samsung and Apple settled the case out of court in 2018.

“Samsung’s culture was extremely confident. They thought that they could do anything, and compete with anybody,” Yoo remembers. “These were people who fought genuine No. 1 companies—Intel, Sony, Panasonic, and so on. And then they won.”

But now, Samsung has lost some of its mojo, Yoo argues. He blames the 2016 controversy around the Galaxy Note 7, whose batteries caught fire and forced an expensive recall. “Samsung could have continued to innovate. But I think they stalled in a way,” he says.

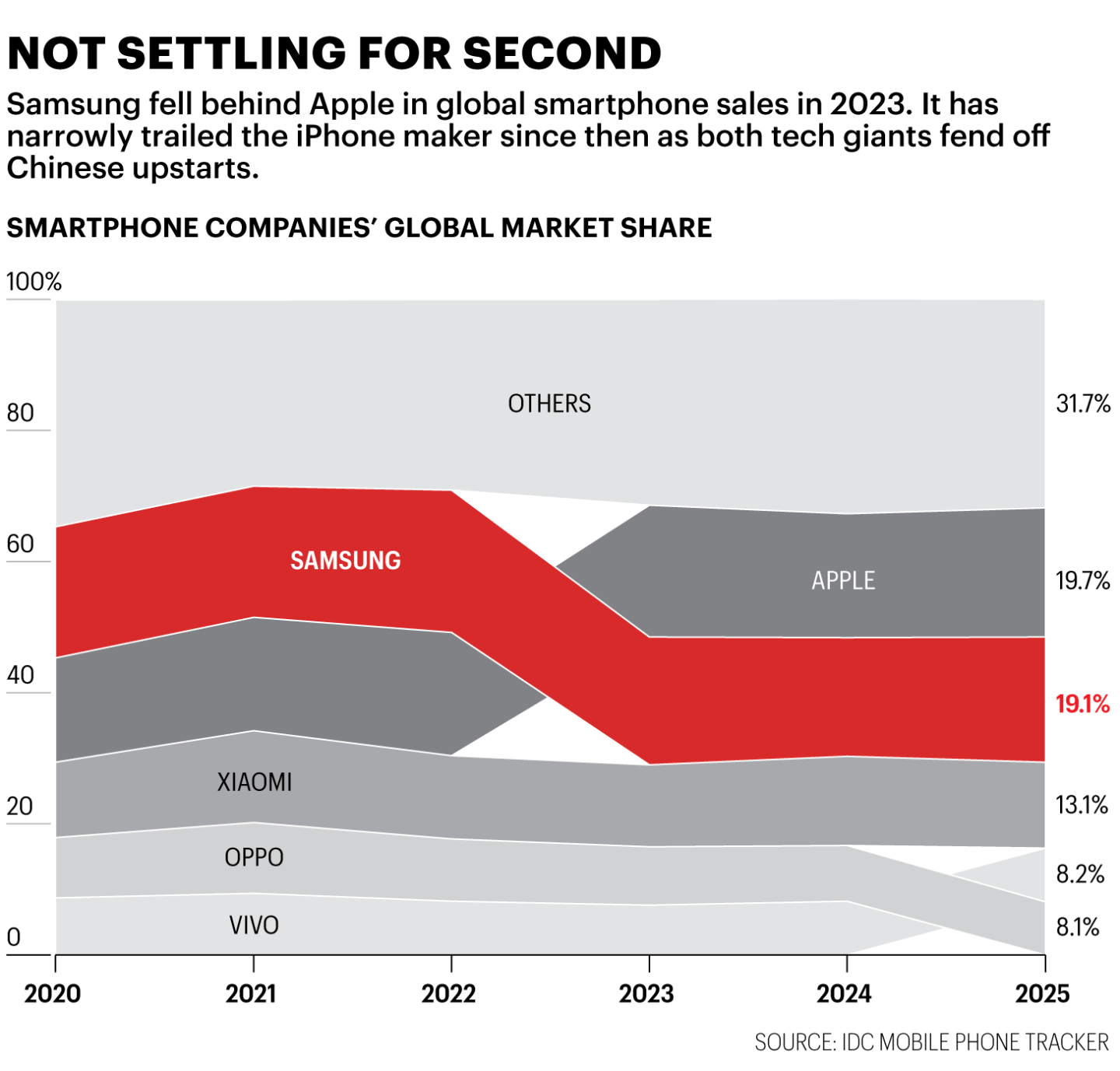

The numbers bear that out. Apple overtook Samsung to become the No. 1 smartphone seller in 2023 and has maintained a slim lead over its Korean rival since then, according to International Data Corporation, a market intelligence firm. And up-and-coming Chinese firms like Xiaomi (for phones) and TCL (for TVs) are starting to encroach on Samsung’s premium markets.

The rise of AI services like ChatGPT and DeepSeek is presenting another challenge to phone designers, whose smart devices don’t seem quite as smart in an age of LLMs and AI agents. Samsung has experimented with AI, such as using it to automatically enhance photos, sometimes to the chagrin of photographers who want something more natural.

Still, phones largely follow the basic design and user interface debuted by the iPhone almost two decades ago. What might a truly AI-enabled consumer device look like? Is it more than just a dedicated chatbot app on a phone? Does the device even need to look like a smartphone at all?

Last year, OpenAI, the ChatGPT developer, hired Jony Ive, the designer responsible for Apple’s most famous products, to start thinking about what an OpenAI consumer device might look like. Yet recent AI devices from others—like the Rabbit R1 and the Humane AI Pin—have flopped as users struggled with price and performance.

Chinese companies may be taking an early lead. In early December, ZTE unveiled the Nubia M153, an “engineering prototype” that boasted full integration with ByteDance’s AI model Doubao. The phone can automatically access apps to fulfill voice commands from its user: for example, booking a car through a ridehailing app, or finding the cheapest price for a given product on different e-commerce platforms. (The phone was enough to spook ByteDance’s competitors, like Tencent, which quickly blocked Doubao’s access to their platforms.)

Samsung is aggressively pushing its AI across its products, with Samsung Electronics co-CEO Roh Tae-moon promising to get its Galaxy AI services onto 800 million mobile devices this year. “We will apply AI to all products, all functions, and all services as quickly as possible,” he told Reuters in an early January interview.

Porcini is still in the early stages of figuring out what AI means for Samsung’s vast catalog of products, and he won’t yet specify how he’ll refresh the lineup. But in an official post soon after his appointment, Porcini talked about building “an ecosystem of experiences” that seamlessly knits together phones, TVs, home appliances, and wearables, and proactively matches what a human user wants and needs, like a fridge that “understands your dietary goals,” or a TV that “mirrors your mood.”

Creatives pitched “design thinking”—an approach in which designers focus on customer needs, rather than constraints or business problems, as the starting point for innovation—in the early 2000s as a way to transform companies and unlock greater sales. When designers failed to achieve those lofty aims, the knives came out, particularly as businesses cut costs in an age of high inflation and macroeconomic uncertainty. One McKinsey survey from 2020 found that only a third of CEOs could say with any certainty what their designers do.

Generative AI puts even more pressure on human designers. On the one hand, designers can use AI to more easily brainstorm and refine ideas. On the other, corporate executives may relish the opportunity to replace expensive human creators with an AI program that can do the job faster and cheaper

Yet Porcini is optimistic that AI will, in fact, reinforce the value that human designers can bring to companies. “Eventually, AI and robots will become a commodity,” he suggests. “Technology is a tool.”

And “in an age of extreme technology, businesses need the best humans more than ever,” he says. “Designers are the ambassadors for human beings. And creating value for humans is one of the most powerful competitive advantages you can build at a company.”

This article appears in the February/March 2026 issue of Fortune with the headline “The star designer reinventing Samsung for the AI age.”